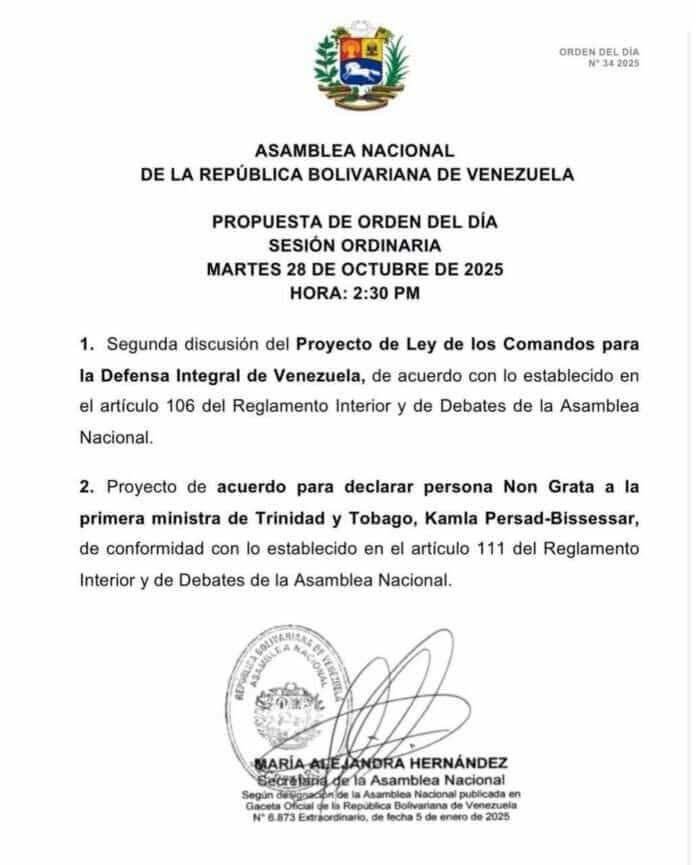

October 28, 2025 – The Caribbean’s cherished identity as a “Zone of Peace” is being tested in real time. Venezuela’s National Assembly has tabled a motion to declare Trinidad and Tobago’s Prime Minister, Kamla Persad-Bissessar, persona non grata, an unprecedented diplomatic strike in CARICOM’s modern history. Once adopted, it would mark the first time a sitting Caribbean head of government is formally condemned by the Venezuelan legislature.

At first glance, this might seem like the latest chapter in Venezuela’s turbulent foreign relations. But for the Caribbean, the implications run much deeper. It signals a shift in the region’s geopolitical temperature, one that blends energy diplomacy, national security, and great-power rivalries into a combustible mix.

Energy and Sovereignty Collide

Venezuela’s move comes amid a rapid unravelling of cooperation with Port of Spain. Only days earlier, Caracas suspended key energy agreements with Trinidad and Tobago, including the Dragon Deal, accusing its neighbour of “hostile alignment” with the United States. The trigger appears to have been Trinidad’s hosting of U.S. naval assets as part of a broader anti-narcotics and security initiative in the southern Caribbean.

For Venezuela, this was more than a routine military partnership. It was a signal that the once-pragmatic energy ally had shifted decisively toward a U.S. orbit, undermining Caracas’s influence at its maritime doorstep. The decision to debate Persad-Bissessar’s status inside Venezuela’s National Assembly transforms diplomatic frustration into a public spectacle. It could signal a deliberate attempt to isolate her politically, regionally, and symbolically. This could play well in light of her recent berating of her colleagues in Caricom.

The Commandos Bill and the Militarisation of Space

Compounding the drama, the same parliamentary session also includes the second reading of Venezuela’s Commandos Bill for the Integral Defense of Venezuela — a sweeping measure empowering special military units to defend the nation’s “territorial and economic sovereignty.”

It’s no coincidence that this law is being advanced at a time of mounting U.S. military presence and increasing diplomatic fragmentation across the hemisphere.

To smaller Caribbean states, the optics are troubling. A militarised Venezuelan coastline just miles from Trinidad’s energy corridor raises fears of miscalculation. It also reopens anxieties about how quickly external rivalries, like the U.S. versus Venezuela can spill into a region that has long prided itself on neutrality and balance.

The Economic Undercurrents

The economic stakes are significant. Trinidad and Tobago’s hydrocarbon sector depends heavily on stable partnerships and regional goodwill. While the country has diversified gas sources, Venezuela’s reserves remain strategically important for future expansion and downstream projects. Any prolonged rift could chill investor confidence and slow regional energy integration, including shared LNG infrastructure and pipeline networks.

For Venezuela, the suspension of energy ties carries its own costs, particularly the loss of foreign revenue channels and goodwill at a moment when sanctions and isolation still bite. Yet the decision underscores a political logic: better to be seen as defiant than dependent.

The fallout may also ripple through CARICOM. Member States that have benefited from Venezuelan energy assistance and associated social programmes under PetroCaribe could face renewed pressure to clarify their positions. It’s a reminder that the region’s economic interdependence can also become its vulnerability.

The Zone of Peace Ideal at Risk

Since 1979, CARICOM has repeatedly reaffirmed its vision of the Caribbean as a Zone of Peace, a buffer against Cold War militarisation and foreign interference. That principle, echoed in the Community’s 2025 declaration just days ago, rests on diplomacy, dialogue, and respect for sovereignty. But today, that ideal is under pressure from multiple directions: from great-power manoeuvring between the U.S. and Venezuela, from shifting alliances among member states, and from the quiet militarisation of maritime borders under the pretext of “counter-narcotics” and “defence cooperation.”

Trinidad and Tobago’s predicament exposes how fragile the balance has become. The Caribbean cannot preach peace while allowing its waters to fill with warships and its politics to fracture along foreign lines.

The declaration of persona non grata may target one Prime Minister, but it tests an entire regional philosophy.

Options for the Region

The region now faces a choice: either react as individual nations or respond as a bloc committed to de-escalation and principled neutrality. CARICOM’s Council for Foreign and Community Relations (COFCOR) should immediately convene a high-level dialogue to reaffirm the Zone of Peace mandate and seek back-channel mediation between Caracas and Port of Spain.

The Caribbean has successfully navigated storms before, from the Grenada intervention in 1983 to the most recent Guyana–Venezuela border dispute. But it has done so through diplomacy, not deterrence. The lesson remains: peace in this region is never automatic. It is negotiated, reaffirmed, and defended daily.

As the Commandos Bill inches toward passage and diplomatic rhetoric heats up, Caribbean leaders must remember that the true strength of the region lies not in the size of its fleets, but in the steadiness of its principles.

Concluding Thoughts

Trinidad’s Prime Minister may yet choose restraint, the dignified silence of a neighbour unwilling to mirror hostility. But the larger question lingers for all: Can the Caribbean continue to call itself a Zone of Peace if it allows its sea lanes to become extensions of external conflicts? If history is our teacher, the answer must be no. Peace requires vigilance and the courage to keep talking when others are preparing for war.