Mexico’s state oil company Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) suspended a planned crude shipment to Cuba, quietly removing a tanker from its export schedule that had been set to sail in mid-January. The cargo, expected to arrive in Havana before the month’s end, vanished from shipping manifests as geopolitical pressure intensified.

On paper, it was a single shipment that was cancelled. In reality, it is a key pressure point in a long-running struggle over energy, sovereignty, and survival.

Oil from Mexico offered short shipping routes, compatible crude, and logistical ease. The supply was predictable, with a workable payment system. It was vital for Cuba’s energy stability and economic base

Blackouts, Fuel Shortages, and a Last Lifeline

Cuba’s energy system is already under acute strain. Reports abound of chronic blackouts and fuel scarcities that have defined daily life throughout 2025 and into early 2026. Power cuts stretch for hours. Transport systems sputter. Public services operate on contingency.

Much of this traces back to the collapse of supplies from Venezuela, once Cuba’s principal energy partner. Venezuelan oil flows have dwindled over time amid production decline, sanctions, and intensified U.S. pressure on tankers and insurers operating in the Caribbean.

With Caracas no longer able to sustain regular deliveries, Mexico emerged as Havana’s last dependable external supplier, sending roughly one tanker per month, estimated at 20,000 barrels per day, since 2023. Mexican officials framed the arrangement as humanitarian assistance rather than commercial trade, a crucial distinction in a sanctions-heavy environment.

The paused shipment is not a marginal adjustment. It severs a stabilising artery just as Cuba’s power grid teeters. For ordinary Cubans, the impact is immediate and tangible: longer blackouts, harder-to-find fuel, strained public transport, and rising pressure on hospitals, water systems, and food distribution.

U.S. Pressure and Mexico’s Diplomatic Tightrope

The timing of Mexico’s decision is not accidental. U.S. President Donald Trump has publicly vowed to cut off oil and financial support to Cuba, declaring there would be “no more oil or money going to Cuba, zero!” The message has echoed across U.S. policy circles as part of a renewed strategy to weaken the Cuban state by tightening access to external energy.

Mexico’s president, Claudia Sheinbaum, continues to frame Mexico’s Cuba policy as a sovereign, humanitarian choice. Yet internal reviews and cabinet-level recalibration suggest a growing concern about U.S. retaliation, particularly as Mexico navigates sensitive trade discussions and a possible review of the North American trade framework.

Mexico’s position is no longer just about solidarity with Havana. It is about balancing regional autonomy against economic exposure to Washington. Energy, once a quiet channel of cooperation, has become a diplomatic fault line.

A 60-Year Backdrop: The Embargo and Energy Vulnerability

To understand why a single shipment carries such weight, one must zoom out. The U.S. embargo on Cuba, imposed in the early 1960s, has spent more than six decades reshaping the island’s economic geography.

The embargo did not simply restrict trade. It systematically narrowed Cuba’s access to global energy markets, international banking and credit and shipping insurance and logistics networks.

The consequences have been cumulative. Cuba endured extreme hardship during the “Special Period” of the 1990s, when the collapse of the Soviet Union erased preferential trade and energy support almost overnight. Austerity became structural, not temporary. Since then, successive U.S. administrations have adjusted the tone of sanctions, but the core restrictions on finance, fuel, and shipping have endured.

Against that backdrop, Mexico’s oil shipments were never just barrels of crude. They were strategic relief inside an economic ecosystem distorted by long-running embargo pressure.

Remaining Oil Supply Options

Cuba’s energy crisis is often framed as a lack of suppliers. In truth, it is a systems problem, created by sanctions, logistics, finance, and geopolitics converging on a small, import-dependent island. With Mexico’s oil now paused, Havana’s remaining options fall into fragile categories.

Venezuela’s oil underpinned Cuba’s economy through preferential pricing and political barter for two decades. That era has effectively ended. U.S. sanctions on Venezuela’s PDVSA had already crippled the oil export industry, including choking supplies to Cuba. Without Maduro, an effective blockade, and with the future of the country’s oil industry under U.S. direction, Venezuela can no longer supply Cuba.

Russia has periodically supplied crude and refined fuel to Cuba, often framed as strategic solidarity. Political alignment is strong, and Moscow has shown a willingness to operate outside Western pressure. But geography imposes limits. Long-distance shipping raises costs, and supplies arrive in bursts rather than on a predictable schedule.

Russia’s own sanctions environment further constrains flexibility and limits the ability to regularly supply Cuba’s needs.

Iran has the technical expertise to move oil under sanctions and has done so in the past. However, the process is costly and complicated and not suited to be a regular source. Shipments rely on ship-to-ship transfers, reflagged vessels, and non-dollar settlement mechanisms. Every delivery, however, is closely monitored. Insurance premiums are elevated. Delays, diversions, and cancellations are routine risks.

Algeria has supplied liquefied natural gas (LNG) to Cuba, helping stabilise electricity generation during acute shortages. LNG can keep power plants running, and shipping routes are shorter than those from Russia or Iran.

While oil is available on global markets, Cuba’s access is distorted by the extensive sanctions architecture: banking access is restricted, insurers avoid vessels bound for Cuba, and traders demand cash premiums or require complex intermediaries, resulting in prices above market norms. Open market purchases are simple, economically punishing, and unsustainable.

Alternative Energy Options

The sudden absence of a single shipment underscores how exposed Cuba remains to forces beyond its control, and why the search for a more self-reliant energy future has taken on new urgency.

Cuba has been quietly accelerating a parallel strategy that speaks directly to the vulnerabilities exposed by the current oil squeeze: a rapid pivot toward renewable energy. While fossil fuels still account for more than 85 percent of total demand, the island’s push into large-scale solar, wind, and biomass is not driven primarily by climate rhetoric but by energy survival.

Over the past two years, Havana has moved to fast-track dozens of photovoltaic parks, expand wind capacity along its northern and eastern corridors, and modernise bioenergy facilities tied to agriculture. These projects are designed to do what imported oil increasingly cannot: deliver power without tankers, insurers, or dollar-clearing banks. In a sanctions-constrained environment, renewables offer something rare: domestically anchored energy that cannot be interdicted at sea or throttled through financial channels.

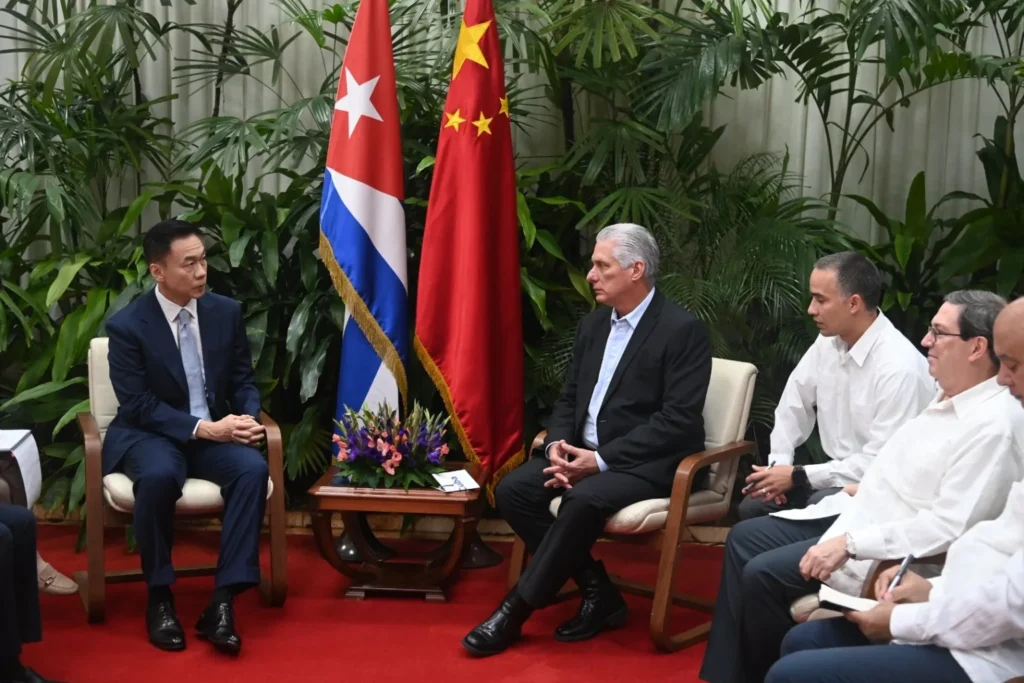

That transition is being underwritten by an expanding circle of international partners, with China at its centre. Beijing has emerged as Cuba’s most consequential supporter of renewable energy, supplying solar equipment, technical expertise, and financing within broader infrastructure cooperation frameworks. As recently as last week (January 22, 2026), President Xi Jinping authorized the delivery of emergency aid to Cuba, including US$80 million in financial assistance.

Russia continues to provide energy-sector assistance, while European partners, including Spain and Germany, have offered technical cooperation, grid planning support, and climate-linked financing. Emerging partners such as India are exploring cooperation in renewables and energy efficiency.

Together, this mosaic of support does not eliminate Cuba’s immediate fuel shortages, but it offers a form of strategic shelter: a pathway to reduce exposure to what is increasingly an aggressive, fossil-fuel-centred pressure strategy by the United States. In the heightened sanctions and blockade landscape, every megawatt generated at home becomes an act of economic insulation.

Look to the Future

For Cuba, this further tightening of energy imports deepens the humanitarian stress that extends well beyond electricity generation. Blackouts mean not only darkened streets and limited transportation but also fragile hospitals operating under contingency plans, stalled manufacturing, disrupted food processing, and mounting pressure on small businesses already strained by inflation and scarcity. Energy insecurity compounds social fatigue, accelerates outward migration pressures, and erodes the state’s capacity to stabilize daily life. International experts suggest that Cuba’s current oil reserves can sustain the economy at best through the end of February.

For the wider Caribbean, Cuba’s predicament is an uncomfortable mirror. Most regional economies remain heavily import-dependent for fuel, food, and finance, with limited strategic buffers against external shocks. The episode underscores a broader vulnerability: small states possess little insulation when energy, banking access, or trade routes are weaponised by larger powers. As the United States advances a more assertive, interest-driven regional posture, Caribbean nations are reminded that their room for manoeuvre is narrow, their leverage limited, and their exposure acute. What happens to Cuba today foreshadows how pressure can be applied elsewhere tomorrow, not through invasion or embargo alone, but through friction, delay, and denial.

For U.S. policy, the renewed hard line reinforces how energy has become a primary lever of influence in Latin America and the Caribbean, aligned with a revived interpretation of hemispheric dominance rooted in Trump’s Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine. Oil, shipping, insurance, and finance now function as tools of compliance, shaping behaviour without formal declarations or treaties. This approach leaves little room for multilateralism and strains regional institutions that depend on cooperation, not coercion, to manage shared challenges such as energy security, climate resilience, and migration.

For Mexico, the paused shipment reflects the high-wire act of modern diplomacy, balancing sovereign decision-making and humanitarian instincts against exposure to the hemisphere’s largest economy.

For others in the international community, the episode highlights the limits of transaction-based, bilateral diplomacy in a world where pressure is asymmetrical and rules are unevenly enforced. While China, Europe, and emerging partners continue to engage through infrastructure, climate finance, and technical cooperation, their ability to offset U.S. leverage remains partial. The result is a region navigating cautiously forward, aware that progress increasingly depends not only on partnerships formed but also on pressures avoided.

Thank you. This was enlightening. Let us hope the rest of us learn from this and urgently make the changes necessary to get away from fossil fuel & trade dependence.

Our very survival and independence are at stake.

Thank you for reading and taking the time to share your feedback. Our region needs to urgently look at realistic options to become more energy resilient

Thank you. The micro states of the Caribbean have always understood the asymmetry that sets them apart from their northern neighbor. Will the Trump administration succeed in crushing the Cuban revolution? When the USSR stood as a defender, Cuba’s genius thrived. Today, the dominoes have shifted. The effort to turn Cuba into a failed Haiti is the object. Domestic order is holding in Cuba. Support for the Cuban government by its people has not been eviscerated. Amid the gloom, that is the glue which has kept Cuba from falling apart. Deep-seated appreciation for decades of development and innovation in Cuba has won it applause globally. What’s next?

Thank you for engaging and sharing your feedback!! Absolutely appreciated