Effective January 21, 2026, Antigua and Barbuda is among the countries affected by the introduction of financial guarantees into the visa process.

Antigua and Barbuda is among a group of countries impacted by the U.S. Visa Bond Pilot Program, a policy measure introduced by the United States Government that allows consular officers to require certain visa applicants to post a refundable financial bond as a condition of visa issuance.

The programme applies only to short-term, non-immigrant travel and does not constitute a visa ban or a blanket restriction on movement. However, it introduces a new financial threshold that some travellers may be required to meet as part of the visa approval process.

How the Visa Bond Pilot Program Works

The bond requirement applies to new applications only and is assessed at the point of the visa interview, not at U.S. ports of entry and not retroactively to existing visas.

It applies exclusively to:

- B-1 visas for business travel, and

- B-2 visas for tourism, family visits, and medical travel.

Consular officers may require a refundable bond of:

- US $5,000

- US $10,000

- US $15,000

The amount is determined at the discretion of the consular officer, based on an assessment of immigration compliance risk.

Where a bond is imposed:

- Payment is not automatic and not upfront

- Applicants are directed to pay only after the visa interview

- Payments must be made exclusively through the official Pay.gov platform

- A direct payment link is issued by the consular officer

The bond is fully refundable once the traveller:

- Complies with all visa conditions, and

- Departs the United States before the authorised stay expires.

Importantly, the bond is a condition of visa issuance, not a requirement imposed on arrival. U.S. border officials do not collect bonds at airports, nor can they impose them on travellers who already hold valid visas.

Who Is and Is Not Affected

The Visa Bond Pilot Program does not apply to all applicants, nor does it automatically affect every Antiguan or Barbudan traveller. It operates as a case-by-case compliance mechanism, targeted at specific applicants rather than entire populations.

Travellers who already hold valid B-1 or B-2 visas are not subject to the bond requirement, and there is no retroactive application of the policy.

Distinguishing Non-Immigrant and Immigrant Visas

It is also critical to distinguish the Visa Bond Pilot Program from immigrant visa policy, as the two operate under entirely separate frameworks.

The bond programme applies only to non-immigrant visitor visas, which are temporary by definition and require proof of intent to return home. These include business, tourism, family, and medical travel.

Immigrant visas, which lead to permanent residence in the United States, are not covered by the bond programme. They are governed by separate eligibility rules, processing systems, and policy decisions, including any pauses or suspensions that may be introduced independently of the bond pilot.

In simple terms:

If visas are not being issued, the bond is irrelevant. If visas are being issued, a bond may be required in select cases.

The bond is therefore a compliance tool for short-term mobility, not a barrier to permanent migration pathways.

What This Means in Practice

While the programme stops short of an outright restriction, it introduces:

- A potential financial barrier to leisure, family, and business travel

- Additional considerations for Caribbean nationals who depend on U.S. mobility for commerce, healthcare access, education links, and diaspora engagement

For small island states such as Antigua and Barbuda, mobility is not incidental. It is deeply intertwined with economic activity, social networks, and regional connectivity.

A Quiet Redefinition of Mobility

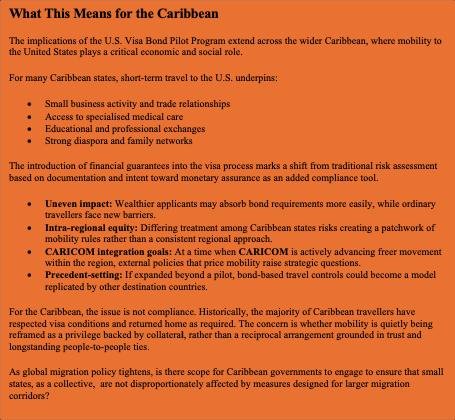

Beyond the technical mechanics, the Visa Bond Pilot Program signals a subtle but meaningful shift in how mobility is being governed.

Rather than restricting entry through outright refusals, the policy introduces financial guarantees as a gatekeeping mechanism, reframing access around perceived risk and ability to post security. While framed as a compliance safeguard, it functions in practice as a quiet means test, one that weighs travellers’ financial capacity alongside their intentions.

For Caribbean societies, where travel to the United States often serves practical needs rather than luxury purposes, the implications are uneven. The vast majority of travellers already comply with visa terms, yet the burden of proof is increasingly being shifted onto individuals rather than systems.

More broadly, the programme raises questions of equity and regional treatment at a time when CARICOM is actively working toward deeper integration, freer movement within the region, and stronger collective positioning in global negotiations.

The central issue is not whether travellers will comply. Most already do. The deeper question is whether mobility itself is being gradually redefined from a reciprocal norm into a privilege backed by financial collateral.